Building a Diet Plan: #1 Calories

Whatever is your fitness goal you need to have a plan. Failing to plan is planning for failure.

So I am going to give you a guide for making the best diet plan, from A to Z. Whether you are a beginner or a veteran in the sport of weight management, this guide will answer all of your questions.

You need to have adequate information in order to have a plan and follow it. When you are missing pieces of the puzzle, your plan is going to fall apart soon.

Now let’s see how that happens.

A guy name John reads an article about diet plans. The article suggests to eat 3 specific meals each day for some time and then his extra weight will be gone. John starts following the plan but after a while, he gets bored and tired of the same foods every day.

One day he says he needs to reward himself for staying on the diet and grabs one slice of cake. After some minutes, he notices that he had eaten half of the whole cake. Disappointed in himself, he thinks he can’t do it. So he stops dieting altogether.

Now we have a girl named Marissa. Marissa reads a series of articles and learns all about diet plans and nutrition in general. She learns about energy balance, macronutrients and how all this fits together. She probably even makes the same diet plan as John, probably with fewer calories since she is a woman, but with the same foods. She gets a little bored after a while but she knows how her physiology and psychology work and why she is getting tired.

She is fully aware of that and she is capable of making any dietary adjustments to keep being on a diet until she reaches her goal. Marissa is good for life since she knows how to structure her diet and always finds ways to make her diet plan work.

We are obviously with Marissa on this one, and we are trying to make people like John, be more like her.

The following guide is heavily influenced by the book “Why Calories Count” by Malden C. Nesheim and Marion Nestle, and the book of Eric Helms “THE MUSCLE & STRENGTH PYRAMIDS”

Now for the basics of structuring a diet plan, we need to know about calories. There’s nothing more basic than calories.

Why Calories matter most

Probably you have heard that for a business to be successful, it needs to have more profits than losses (hence the P&L statement). That is the first thing anybody interested in a company would ask. A company could not operate without measuring finances.

Well, the exact same thing applies to our body. Although most of the time, we want it to go on losses rather than profits.

The profits in this equation are the calories in, and the losses are the calories out.

Calories are a measure of energy and are commonly used to describe the energy content of foods.

“Calories in” is the food we consume in order to provide our bodies with energy. “Calories out” is the energy we expend on various activities, even digesting the food we consume can make us spend some energy.

So when we eat fewer calories than we spend, we are in caloric restriction. When the opposite happens, we are in caloric surplus.

But why calories are the most important part of a plan?

Because as you may have guessed it’s the dominant factor of your weight management. Not macronutrients, not eating 6 versus 2 meals, not a whey protein from the supplement store and certainly not eating for breakfast only oats and egg whites. I can assure you, that you can lose weight by eating 1 bag of potato chips a day.

This wouldn’t be healthy obviously for a lot of reasons and certainly not optimal, but the result would be that you lose weight. Since a bag of chips (10 ounces of Lay’s classic) is around 1600 calories and most probably you are expending more than that.

Mini disclaimer: all parts of a diet plan matter, but you need to prioritize.

- Calories

- Macronutrients

- Micronutrients & water

- Meal frequency & timing

We need to have calories in check before we look into any other aspect of a diet plan

So let’s get a bit scientific and learn more about calories

What is a calorie

The strict definition by chemists is:

One calorie is the amount of heat energy needed to raise the temperature of one gram of water by 1 °C, from 14.5° to 15.5°, at one unit of atmospheric pressure.

Now there might be a misconception about chemistry and food because when talking about calories in foods, we’re talking about kilocalories(kcal) or Calories, with a capital “C”. The reason is that if we used regular calories for foods, we would be expressing daily calorie requirements in a number of millions. consider 2,500,000 instead of 2,500. Not that practical.

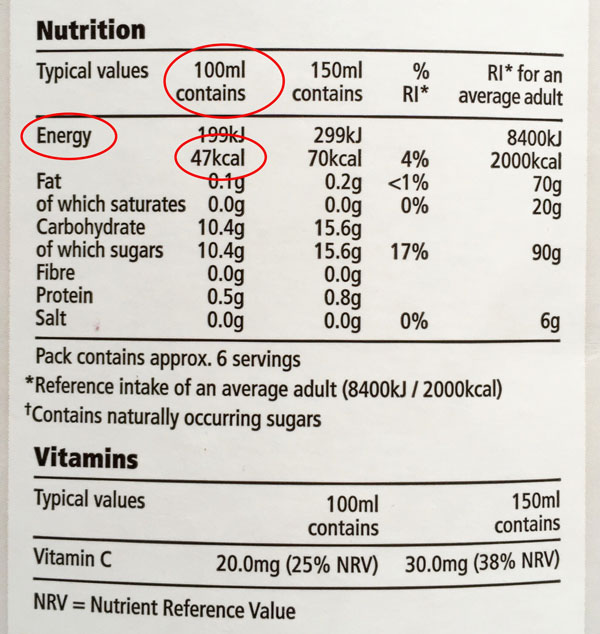

So we might call them calories but scientifically, they are kcals. That’s why the food labels need to use both terms kcals and Calories. Don’t worry, we will be using the word “calories” and we will mean kcal without any problem.

A question may arise of why labels have also kilojoules or kJ. The reason is that everywhere else in the world, but the USA, people are using the SI metric system (French: Système international d’unités, SI). So in order to be compliant with the rest of the world, the USDA decided to use both metric units of energy, kcal and kJ. Calories dominated the food industry and nowadays we don’t really care about kJ other than in chemistry.

Some food labels have both units and some have only kcal.

So the next natural question is that might arise is how did we come up with the concept of calories in foods.

How do we count calories in foods

We began calculating the energy in food since the early 1600s. But the true awakening came with the discoveries of an American Chemist from New York, around 1880.

Enter Wilbur Olin Atwater. He is probably the most important person regarding our whole system of counting calories in both consumption and metabolism. But let’s see a little bit why.

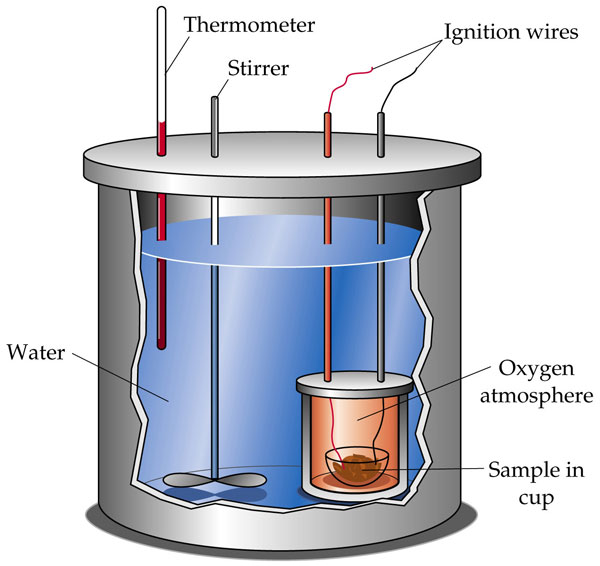

Up until Atwater, the way we were measuring calories of foods was by a device called bomb calorimeter.

Here’s how the bomb calorimeter works:

Food in the steel chamber (bomb) is ignited and burned (oxidized) to completion. Calories are calculated from the heat transferred to the surrounding water.

This is the golden standard for actually measuring calories in a food. The only problem with it is that it calculates the “potential” energy of the food and not the actual energy we use from it.

Energy is being lost in 3 ways:

- Excretion in urine

- Excretion in feces due to incomplete digestion

- Inefficient metabolism

There are also some losses that occur in sweat but they are minor.

In order to understand how calories work, we need to know a little bit about macronutrients. The fundamental molecules of energy in food. Protein, Carbohydrates, and Fat.

Protein is used by the body for growth and tissue repair. Carbs are the body’s main source of fuel and Fat is the densest form of energy and it helps us absorb fat soluble vitamins. There is much more to know about macronutrients, but we will deal with that in the next part of this series.

So urine losses happen due to protein. Carbs and fats are completely oxidized to carbon dioxide and water. But proteins also contain nitrogen, which is excreted in the urine. The bomb calorimeter actually oxidizes completely the nitrogen just fine, but our bodies are using only a part of it.

As for losses in feces (toilet losses :P), it accounts for approximately 3% of total calories. Atwater measured macronutrients in feces as well, and after that, he came to a conclusion of final values of calories for the macronutrients.

The famous Atwater values:

- 4 calories for 1 gr of protein

- 9 calories for 1 gr of fat

- 4 calories for 1 gr of carbohydrates

Just for completeness, even the Atwater values are not completely accurate, since different foods have different absorption rates. Like protein from meats, for example, provides us with 4,25 calories per gram while protein from vegetables gives us around 2,9 calories per gram. That’s also how the concept of bioavailability came. Bioavailability, in nutritional sciences, is the degree in which we absorb the nutrients of foods.

So despite efforts of coming with a more accurate way of measuring calories in foods, the Atwater values persist till today. We are better of using a system that is pretty accurate when you consume a variety of meats and vegetables, in order to even out the difference. We prefer to be simple rather than 100% accurate since the actual difference is not that important.

Lastly, inefficient metabolisms is a per person issue, as people with various diseases, pregnant women, or simply people with different genes may respond differently to various foods. The variability though could be as much as 5% so it’s not totally worth it to deal with.

The last thing you need to know about metabolism is that we use up calories from food in 2 pathways.

- Heat losses

- Basal metabolism and Muscle work

The basal metabolism part and muscle work could be divided further into:

- Energy cost of body weight

- Energy cost of physical activity

- Energy cost of fidgeting

- Energy cost of mental effort

The first 2 can be very significant actually extra body weight can have a big effect on the calories we end up using as well as the physical activity. not to mention that physical activity has an extra cost of EPOC (excess post-exercise oxygen consumption). The energy you are using after physical activity. It isn’t much. At most the extra EPOC energy accounts for an additional 15 percent of calories expended in the activity itself, and that is on the very extreme.

The cost of fidgeting might seem silly but it might account for an impressive 100 to 800 calories a day[1]

Lastly, mental effort is not that intense. Francis Benedict, on 1930, published a paper where he concluded that mental effort has little effect on the brain’s energy requirements and the extra energy we end up using, comes from the rapid heartbeats and clenched muscles.

Now that we have defined calories, we should learn how many calories are actually in foods.

How many calories are actually in foods

The USDA (U.S. Department of Agriculture) has made a terrific job of documenting food information for approximately 9000 foods. There is also this page where you can search for all the details of each food.

For any other food that is commercial, we should trust the food labels by the manufacturers of those foods.

What someone would ask is if we should trust those labels.

The thing is, that labels are pretty accurate in the numbers of absolute calories or grams of macronutrients. The only part, that we need to be skeptic about, is the percentages of daily requirements. This is a bit arbitrary and each one of us has different caloric needs. So you only need to care about the calories and the grams of protein, carbs and fats and their derivatives like saturated or unsaturated fats, and sugars, fibers.

In a following part of the series, we will learn more about the importance of these micronutrients.

Nowadays the food manufacturers don’t calculate the calories of a product directly, but they are using the information from the ingredients of each product. Although cooking can affect the energy we can get from foods, producers only need to care about the calories that exist in the raw product.

For example, potatoes have a bigger amount of calories when boiled than raw

| Food | Calories |

|---|---|

| Potato, flesh and skin, raw (100gr) | 77kcal |

| Potatoes, boiled, cooked in skin, flesh, without salt (100gr) | 87kcal |

The difference is very small but it is worth mentioning

Another interesting thing is if all restaurants could have information about calories in their dishes, it could make our lives much easier. It would, at least, give us the incentive to be aware of the calories we consume.

Actually some restaurants, are including caloric information in their catalogs.

New York was the first city to require calorie labels on restaurant menus. In 2006 the NYC Health Department proposed requiring quick-service chain restaurants with more than fifteen units within city limits to post calories on menu boards. The New York Restaurant Association strongly opposed this idea, arguing that calorie labeling would be impractical, expensive, and an unconstitutional violation of free commercial speech. It filed lawsuits. After much legal wrangling, the courts ruled in favor of the city, and menu labeling went into effect on July 19, 2008.

– Why Calories Count, by Malden C. Nesheim and Marion Nestle

So with our education info about calories in check, let’s see how many calories we need.

How many calories do I need

The calories we expend is mostly known as BMR or basal metabolic rate, the rate of calories we need to maintain our weight without any activity. There are many equations for actually calculating BMR but the reigning ones are:

- Harris–Benedict equation

- Mifflin-St Jeor equation

- Schofield equation

- Katch-McArdle Formula

The first 2 algorithms are using weight, height, and age while the second one uses only the weight of a person. The last one is taking into consideration your body fat percentage as well.

We will take me as an example to check how these algorithms work and what are the results.

My current stats are:

- Weight: 84kg

- Height: 178cm

- Age: 27

- BF: 12%

| Method | Calories |

|---|---|

| Harris–Benedict | 1914 kcal |

| Mifflin St Jeor | 1822 kcal |

| Schofield | 1957 +/-153 kcal |

| Katch-McArdle | 1966 kcal |

Give or take my BMR is about 1900 kcal. I personally trust the last one as it takes into consideration the body fat percent and as you get leaner but relatively having the same weight, you are expending more calories. But in most cases, you pick one and go with it.

The next issue is what amount of calories we would need based on our activity levels. There are modifiers again which we have mentioned in a previous article

| Activity | Modifier |

|---|---|

| Little or no exercise | BRM x 1,2 |

| Exercise 1-3 days per week | BMR x 1,375 |

| 3-5 days per week | BMR x 1,55 |

| 6-7 days per week | BMR x 1.725 |

| Twice Per Day or Heavy exercising | BMR x 1,9 |

So we have an approximation of the calories we need to maintain our weight.There is a better method to calculate our energy expenditure more correctly and it is by tracking the calories of the food we eat and our weight. This may take a month but it is generally more accurate.calories we need to maintain our weight.There is a better method to calculate our energy expenditure more correctly and it is by tracking the calories of the food we eat and our weight. This may take a month but it is generally more accurate.

Example. A person with a BMR of 1900kcal, working out 3 times a week, would need 2612,5 kcal. And this is called our TDEE (total daily energy expenditure).

There is a better (more accurate) method to calculate our energy expenditure more correctly and it is by tracking the calories of the food we eat and our weight. This may take a month but it is generally more accurate.

I would suggest to go with the results of the equation for the time being and then adjust the calories if needed. Although the suggested calories coming from the equations are usually correct and very close to accurate.

The next part is to determine how many calories we need for fat loss and how many for muscle gains.

How many calories for fat loss

The general recommendations for fat loss, suggest that we lose 0.5-1kg (1-2lbs) per week. In theory, 1kg (2lbs) of adipose tissue is equal to 7000 calories. Which means that for losing 0.5-1kg (1-2lbs) of weight, we need to consume 3500~7000 less during the 7 days of the week, or 500~1000 fewer calories per day.

Now if you want to go slower you would go for a deficit of 500 calories per day. A deficit of 1000 calories, is a little on the extreme, as most people who go that hard, end up not following the diet. My opinion is to go in the 500-750 range.

Example. If your TDEE is 2000 calories, you would go for 1250 to 1500 calories daily.

How many calories for muscle gain

Building muscle is a much slower process. Therefore, we shouldn’t have the same amount of calories in surplus that we needed in losing fat (eg. 500 to 1000 calories). Suggestions for muscle gains are in the 250-500 range.

Example. If your TDEE is 2000 calories, you would go for 2250 to 2500 calories daily.

The reason is that when building muscle you want to gain as little weight as needed, because if you go above a certain body fat percentage, your body is not operating optimally for muscle gains.

When you’re on the lean range (around 10% BF for men, around 20% BF for women) you are more insulin sensitive and you get a better use of calories. Meaning that more calories end up in building muscle than if you are on the not so lean range (above 15%BF for men, above 24% BF for women).

So you want to remain fairly lean but still gain some weight. Total body recomposition (losing fat while gaining muscle) is extremely hard to achieve unless you are on the beginner stage or using drugs. A good case is the protocol of Lyle McDonald in the UD2.0 book but that’s more advanced and we may need to discuss it another time.

The last part is about asking if we should consume different amounts of calories depending on if we train or not that day.

Should I have different amount of calories on days that I work out

No, and yes.

The short answer is no because the calories you are expending during a 1-hour workout are somewhat 200-300 calories more than if you were sitting at home. So there’s not much difference when we’re talking about some weeks of dieting.

There has been some benefit through calorie partitioning between workout and non-workout days. Having some extra calories on the days you workout, minimizes the effect of protein breakdown due to training[3]. Remember that when you train you are both triggering protein synthesis and protein breakdown. That is also the source of so many info around the post workout nutrition. Post workout shakes target the lowering of the protein breakdown(by having carbs in the shake) and increasing protein synthesis by consuming whey protein.

So if it doesn’t complicate things for you, sure, have some carbs during the workout days and up the calories but remember to reduce further the calories on the resting days.

Calorie partitioning around workout time is also not that important compared to the total calories in a day. There is some benefit though if you consume most calories after training, as you are more sensitive to use these calories for protein synthesis and preventing protein breakdown. This has a greater benefit when you haven’t consumed enough calories before and your blood sugar is low.

One tough part of the equation is that when you reduce drastically your calories before a workout you may not have enough energy to workout with the same intensity. So you need to take into consideration that as well. My recommendation to keep it simple and when you feel confident enough, go the extra mile.

Here’s the next part in the series about macronutrients of foods and we can adjust our diet plan to make the best of use of proteins, carbs, and fat.

Is there something more you would like to know about calories? Let me know in the comments